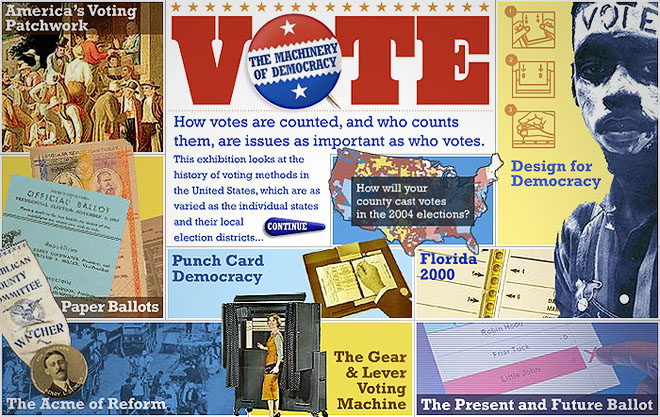

This is a website Behavior made for the Smithsonian’s American Museum of National History during the 2004 Presidential election campaign. It is the web companion for Vote: The Machinery of Democracy, an exhibition of artifacts from America’s long and colorful history of voting technologies.

It was a fascinating physical exhibition. And I’m still proud of our interactive exhibition, too (both the Flash and HTML versions). It’s just as relevant today as it was four years ago in our first post-chad Presidential election (although the interactive map is a little out of date by now — to see a more up-to-date but less-detailed view of how voting technologies are distributed today, use the SciFi Channel’s new map from their surprisingly-good coverage of this topic).

As tomorrow’s historic election approaches, and many Americans will find this year’s voting user experience to be different than what they might be used to, I think it’s helpful to reflect upon the long and complex political and technological paths that got us here. For some colorful tales from yesteryear, see this New Yorker article from just last week. And it’s probably a good idea to learn where we are today: this New York Times article from January 2008 is a great place to start.

The Politics of User Experience

I just want to add one more thing, speaking as a user experience design professional:

It is a profound embarrassment to our profession that touch-screen voting exists at all in our country. It is an inferior system in every thinkable way, including — right up there with reliability, security, and cost — pure empirical usability. User experience experts should be up in arms over the very existence of these machines. Except perhaps for assisting with certain special needs voters, there is no excuse for a state government to have purchased these machines except for either old-fashioned corruption or a sad, abject gullibility for slick marketing presentations by election machine company salespeople. We Americans who call ourselves usability advocates should make it a goal to rid the USA of these machines by the 2012 elections. Who’s with me?

Comments

6 responses to “Vote: The Machinery of Democracy”

cool – looks like an amazing exhibit and site, will check out.

chris, can you go into more detail about your misgivings on touchscreens for voting? i have never used one (my state still uses paper ballots, don’t get me started)

thanks,g

Well said! The confidence in the electoral process here must be restored.

On the Diebold touchscreen machines – is it really a usability issue? The problems would have been uncovered with some simple QA testing, had it been carried out properly.

http://icanhaz.com/calibration

I wonder if Diebold does refunds or just credit notes? 😉

@Harry You’re right that the calibration problem is in large part a QA issue.

It’s also a technology issue: It is obviously possible to make touch screens that don’t require calibration.

It’s a safety issue, too: The touchscreens immediately convert your vote to bits, whereupon it can be altered by erroneous or malicious software.

It’s a confidence issue, too. See above.

But it is also a usability issue, to me. Touchscreens are prone to error from inexperienced users, or people with physical problems. Confirming your vote, changing your mind mid-process, requires navigating a UI, and we all know how bad that can get. Only so much information can fit on a screen at once, leading ballot designers to practice some dirt-poor information design.

I also focus on usability for the election officials: Training officials to calibrate a touchscreen voting machine is probably pretty tough. Helping voters use the machine is probably a chore. Setting up the interface for each new election is likely a pain in the neck.

The best solution is a (large) paper ballot that you fill in with a pen or pencil, and that is optically scanned for an initial count, and ideally hand counted later for certainty or to settle contested races.

Everyone who has gone to school knows how to fill out a paper test form. Mistakes are easy to spot and either immediately correct or in extreme cases voters can simply have the ballot replaced.

It’s also better on all the other fronts. It provides confidence. It’s cheap as hell. It’s easy to update (print new ballots). It provides a permanent record, so even if the counting machines are hacked or broken the ballots themselves still exist and can be counted again, even without machines.

There’s not a single way in which touchscreens are superior to paper except (perhaps) for people who have special needs. It’s just a fancy doodad that foolish election officials were bamboozled into buying. We should stop trying to figure out how to make touchscreens better or easier to use and focus on getting rid of them completely.

Seriously, we should be using pencils and paper for the next hundred years. Not using new technology for no good reason.

You’re right of course, Christopher 🙂 In this case by saying “It’s not a usability issue” I meant that the problem was so glaring, it stuck out like a sore thumb and would have been located by one person simply running through the actions 10-20 times. This puts it more in the class of ‘bug’ than ‘usability issue’.

But the whole raft of other broader issues you bring up are interesting to think about. I’m surprised the whole system hasn’t received proper attention from specialists (like us) – other safety critical systems have (ATC, cockpits, etc), so why not this?

Hi Chris. Congrats on the election of a new president.

Ever since 2000, I’ve been reading progressively amassed evidence to lead me to believe the Diebold voting machines were little more than bare-faced partisan opportunism, not unlike most post 9/11 Bush policies.

1.) Diebold is heavily funded by Republican party donors, but has no funding coming from any Democrat-sponsoring organizations.

2.) Nearly all of the errors reported on Diebold machines during the past 8 years have been the machine switching a vote from a democrat to a republican.

3.) Diebold got in a spot of trouble back in 2004 for installing software onto their machines which allow data from the voting machines to be accessed (and modified) remotely.

4.) Apparently, these voting machines are as easy to open up and modify as a standard desktop PC.

The good news is you may get your wish anyway– According to some of the news reporting that crossed the pond, many American voters in many districts were made to use paper ballots when the machines broke down or the queues became too long.

If I were to put bets on this sort of thing, if this horrible track record continues, Diebold will be forced to rethink its entire system.