A running theme here at graphpaper.com is the debunking of shoddy research methodologies and junk science used to lend authority to and help guide decisions in the design professions. I want to encourage my readers, and the industry as a whole, to (a) stop being so gullible about the research they hear about in the press, and to (b) stop performing meaningless research themselves.

Ultimately my objective is to end the cycle of requiring designers to back up their recommendations with the kind of research or data that cannot be accurately or meaningfully collected, a cycle that forces designers and consultants to produce mountains of bad research. Either do the research correctly and make decisions based on sound science, or don’t do it at all and make your key decisions based on wisdom and experience. No research is better than bad research.

Today’s episode attacks addresses the field of advertising research.

Making Up Numbers

I am a man of very little faith in most quantitative research — not because I don’t believe in numbers, but because, usually, when you scratch the surface of a quantitative research report you will find blatantly subjective or qualitative data being used as the basis for the quantitative data.

Don’t get me wrong, I love qualitative research. But for execs who seek cold, hard numbers, qualitative research is often meaningless and untrustworthy. It is seen as fluffy psychobabble or artistic/creative posturing. So when a designer or a researcher wants their insights to be taken seriously, they often feel the need to “translate” their extensive subjective insights into objective numbers, a process that I think is just another flavor of bullshitting.

Here is a simple made-up example of what I mean by “translating” qualitative research into a quantitative report:

I conducted a study on the subway this Monday morning. I examined 50 people’s faces to see if they looked happy or sad. 15 looked happy, and 35 looked sad. Can I say, then, that 30% of the commuters in my study were happy? Sure. But only if you trust my judgement in reading people’s faces. The numbers are a smokescreen — the real insight, the real magic, is occurring in my personal examinations of people’s faces. My own opinion is the linchpin of the whole “study”. If that one part of the process is unreliable — and you have no way of trusting that it isn’t — then the final numbers are also worthless.

Advertising that “Works”

So now here’s a real-world example with similar underlying flaws: An advertising industry study released recently contends that ads that “tell stories” are more effective than those that do not. Sounds interesting. The methodology sounds pretty science-y, too:

Thirty-three ads across 12 categories—from brands like Budweiser, Campbell’s Soup and MasterCard—were analyzed by 14 leading emotion and physiological research firms. The research tools varied from testing heart rate and skin conductance of the ad viewer to brain diagnostics.

The study was looking for patterns among those ads that work better than others. Here’s an example conclusion:

One such pattern was that a campaign like Bud’s iconic “Whassup” registered more powerfully with consumers than Miller Lite low-carb ads that essentially just said, “We’re better than the other guys.” Why? Because Bud told a story about friends connected by a special greeting.

There are many bells going off in my head reading this. Who is to say that “Whassup” tell more of a “story” than the Miller Lite ads? I remember those ads, and they hardly meet my definition of “story” (a story is something in which, you know, things happen). So it begs the question of “what is a story?” We have to trust the researcher’s opinion on that, I guess.

Secondly, how do they know one ad “works better” than another (this, of course, is one of the advertising industry’s biggest existential questions, right after “does advertising work at all”)? What does “registered more powerfully” mean, exactly? Is that even measurable?

This study used “heart rate and skin conductance”, presumably to mitigate the kind of subjective judgement in my face-reading example above. But what exactly do those physiological conditions have to do with the effectiveness of an ad? If my heart rate goes up, for example, does that mean that I am supposed to be more inclined to buy something? Or is it the exact opposite, that physical excitement indicates hostility to the brand while calmness indicates receptiveness to the brand’s emotionally-compatible values?

It sounds like we’re supposed to assume that there is a meaningful correlation here, but I am extremely skeptical. We must question every little aspect of the so-called scientific studies we read, because if any single part of a study is fundamentally flawed then the whole thing is worthless.

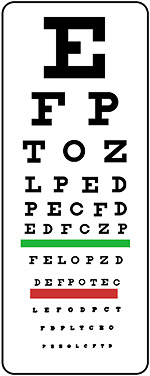

Fundamental to the advertising study is the theory that a person can watch an ad and that researchers can then determine if the ad “worked”, in the same way an opthamologist can put lenses in front of your eyes and determine if you can read the eyechart or not. This idea that an ad “works” when it makes you more inclined to buy something is called “purchase intent”, and it is an industry standard term:

In Campbell’s “Orphan” ad, it is about bringing together a mother and her foster child.

Ad research firm Gallup-Robinson, Pennington, N.J., found that the spot, which showed a little girl’s sadness and anxiety melt away into a soft smile once she was given a bowl of soup, generated 80% purchase intent. Most viewers measured said it was believable.

A similar study from Ameritest, Albuquerque, N.M., found it received 42% purchase intent compared to a category norm of 33%.

Okay, big alarm bell here: 33% is the category norm for purchase intent. WTF? Is that supposed to mean that 33% of people who watch the ad actually intend to buy the product? This defies all credulity. The ad industry, of course, loves to pat itself on the back, but 33%? (Maybe I’m just projecting, but I can’t think of more than one or two ads in my life that have ever succeeded in producing a “purchase intent” in me at all.)

What’s more, how do they determine “purchase intent”? Is it from simply asking the test subjects “Do you want to buy this”? If so, maybe the fact that an ad is funny increases the likelihood of answering the question positively, but ultimately has no effect on whether the purchase actually occurs. Is there any evidence that “purchase intent” has any bearing on “purchasing” at all?

Probably not. My favorite paragraph is the last one:

The study does not discuss the ROI of the ads for their marketers. Mark Truss, director of brand intelligence at JWT, New York, said the storytelling theory is correct, but the industry still lacks a way to prove it. “Without the tools to measure and link back to business metrics, marketers and advertisers are not going to embrace [this approach].”

In other words, it’s all crap. Cheers to Mark Truss for, in essence, openly arguing based on his own experience and wisdom instead of relying on the junk science. I’ll always put more trust in imperfect but honest people than in dishonest or meaningless numbers.

Comments

5 responses to “Lying with (Advertising) Statistics”

I’m totally with you on this. Quite simply, the emperor has no clothes (with regard to the ‘scientific’ studies and pseudo-quantitative results). The Bud ad “worked” because to this day, I can recall it, and recall that it was a Bud advert. As a drinker of beer, I have *zero* “purchase intent” for the product, but it did promote brand awareness. Of course, once a brand has achieved critical mass, does “brand awareness” really matter?

Screw “purchase intent”. How about “purchase made”? I *intend* to make a giant Thanksgiving dinner for friends in Boston, but it’s probably not going to happen. Something about “The road to hell is paved with good intentions”.

Intent doesn’t garner revenue, *sales* generates revenue.

Life would be much better if the advertising agencies cut the crap, and just stopped using pseudo-science to validate their exorbitant hourly rates. There is nothing wrong with paying huge bucks to get a memorable advertisement that puts the brand into the brain of those who witness it. That *is* the end result, as far as the “job” of the advert.

The frustrating part of these studies is that you can’t fully inspect them. I want to see the methodologies, testing plans and final data recorded. As far as I can tell, I never will, but I *will* be able to buy a white paper for $300 that covers the topic. That to me is the complete opposite of “scientific.”

@Noah:

Usually (although true, not always), those $300 white papers do indeed list their methodology and selected excerpts of the raw data.

Of course, with something like that, there is no “try before you buy”, so you pay, and discover their methods are indeed madness.

great article:)

if everyone listens to statistics, we would most likely not see some of the groundbreaking design work around us today.

statistics is just data. the crux still lies in the intrepreter in making us of the data:)

I think I agree, but the question is which of all the bulls— do most people buy. Sorry but I got to eat.

Buzz