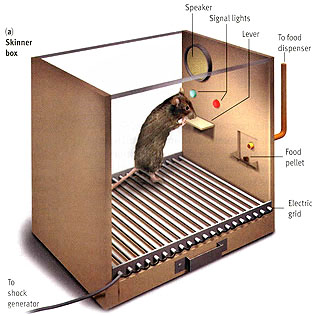

The classic Skinner box experiment.

A comment by Steve Baty on my recent series about design research got me thinking about the fine art of experimental research design:

Where research (in all forms) becomes a waste of time and effort is when the research design and methodology applied invalidate the conclusions _before_ they can be drawn.

One of the things that defines a great scientific thinker is their ability to design and construct meaningful experimental methodologies. Defining the terms and tools of an experiment in such a way as to focus on just the right question while excluding bad data, well, this is where science becomes a high art. Whether it’s physics, medicine, psychology/neurology, human behavior, whatever, the structure of a great experiment is often as interesting, surprising, and elegant as the plot of a great novel — and the insights such experiments reveal are often astonishing.

Sometimes the results of powerful experiments open more questions (often deeper, and more significant questions) than they answer.

I think of things like the Turing Test (measuring the quality of an Artificial Intelligence) or the Double-Slit Experiment (illustrating the quantum nature of light). One of my favorites is a kind of test for autism:

Typically, the child watches two characters in a scene. The first person (A) places some chocolate in a drawer. A leaves the room and B (the second person) moves the chocolate to another drawer. A returns and the observer/child is asked to guess where A believes the chocolate is. Young children (< 3 years) and persons with autism mistakenly think that A will look in the new drawer, whereas older children will correctly claim that A will look in the old hiding place.

Another favorite of mine is the controversial experiment by Benjamin Libet in which it is shown that humans begin an action a full half a second after before their conscious mind makes the decision to act. A shocking conclusion, one that throws our understanding of consciousness and free will for quite a loop. But how in the world can this be measured? Libet’s methodology is ingenius:

Libet asked his experimental subjects to move one hand at an arbitrary moment decided by them, and to report when they made the decision (they timed the decision by noticing the position of a dot circling a clock face). At the same time the electrical activity of their brain was monitored. Now it had already been established by much earlier research that consciously-chosen actions are preceded by a pattern of activity known as a Readiness Potential (or RP). The surprising result was that the reported time of each decision was consistently a short period (some tenths of a second)after the RP appeared.

What are your favorite scientific experiments? I’d love to hear about them.

Comments

3 responses to “Elegant Experiments”

We can’t forget the famous Geiger-Marsden experiment (aka Rutherford’s gold foil experiment) which pretty much lead to the discovery of the atomic nucleus.

Or, how about Gregor Mendel and his peas, leading to the idea of dominant and recessive genes?

Both well-designed and executed experiments in my estimation.

Those are good ones. Sometimes the best ones are the really old ones, the ones where the setup for the experiment can be done by just about anyone. That’s why I like the autism experiment and other simple social constructions that reveal deep insights.

I’m a big fan of the Milgram experiments. Stanley Milgram showed that normal people will do almost anything that someone in a white coat tells them to do — without question….