I attended a fascinating IA Summit presentation by Molecular’s Steve Mulder called “Bringing More Science to Persona Creation“. Lately I’ve been pretty interested in how different companies approach user personas, so this was a must-see for me.

I was impressed with Steve’s insights into user persona creation, but this was tempered by a fear that, if taken too literally, Steve’s perspective on personas might actually do as much harm as good to the adoption of personas more generally as a powerful design tool.

A Brief History of Personas

User Personas, defined simply, are short profiles of typical users of a product or web site, intended to help the design team reach a meaningful understanding who their end users really are. I’ll assume that if you’re reading this, you already know something about personas.

Alan Cooper introduced the world to User Personas in his classic book “The Inmates are Running the Asylum“, and since then it seems like thousands of companies have at least tried the technique in the hopes of building better products for their customers and employees. Today, many companies (including Behavior) use personas as a core part of their user-centered design toolkits. In 25 pages, Cooper ignited a revolution.

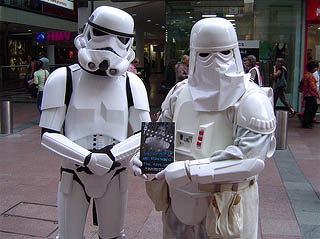

Sean Coon assigned John Ford to photograph his copy of Inmates around the world. This is the latest and best addition to the collection.

Or did he? I would argue that while Cooper did ignite something, user personas are still the subject of far too much confusion and debate in the user experience design community. There are still wide open questions about what personas are for and how we should use them. Are user personas being used correctly? Are they being used enough? The answer to the second question, to me, is a resounding NO, we’re not using them enough. The answer to the first question, to Steve Mulder, is also no: we’re not using personas correctly because we’re not being scientific enough in the way we create them.

And that’s where I think we might have a problem: If Steve’s advice is taken too far (and he’s not the only one saying it), if personas must be be approached more scientifically in order to be valid tools, then fewer of us will use them on our projects. The more “scientific” personas are required to be, the less likely they are to actually be used. I’ll explain…

The Problems with Personas

Steve acknowledged the deep reservations most information architects have with creating user personas: While most of us are immediately drawn to the potential power and usefulness of personas in theory, we constantly wring our hands over the fact that user personas are, at least in the way they’re currently conceived, largely seen as potential fabrications. Works of fiction. And we know it. And our clients know it.

To information architects steeped in the ideals of user research, usability testing, and empirical methodologies, creating user personas from scratch is unethical and even heretical. Making up characters might be okay for Jayson Blair or James Frey, but not for real user advocates.

The preferable alternative, Steve says, is to craft your personas using a more “scientific” approach: to use a variety of powerful empirical tools to remove as much guesswork and speculation from the task as you can, and to base your personas on actual users, their real goals and needs, and their real behaviors. In his presentation, he described many different ways one can make one’s personas more real and more scientific, including quantitative and qualitative user research, surveys, interviews, log analysis, contextual inquiry, CRM data analysis, and more.

This urge, at least as I see it, is what Jesse James Garret called “lab coat IA”: We strive to ground our design decisions on empirical truth in order to avoid arguments based on personal taste and individual idiosyncracies. In his 2002 essay ia/recon, he writes:

The current fashion in thinking about information architecture is that the only good architecture is one that has been built upon a foundation of pre-design user research, and validated with a subsequent round of user testing. But the conflation of architecture with research — and the conclusion that one cannot exist without the other — is a deceptive oversimplification.

At best, we are merely deceiving our clients. At worst, we are also deceiving ourselves.

I agreed with Jesse at the time, and I agree now. To be fair, though, Steve freely acknowledges that there’s never really “proof” that your personas are “real”: No matter how much research you do to make them real, they still require a little fudging, a little inspiration, and a little expert insight to make them truly useful. There is always an art to it. The data will merely permit you to be, in Steve’s words, “less wrong” than if you didn’t have the data.

In theory, of course, Steve is absolutely right that “scientific” personas are better than non-scientific ones. He’s right that many IAs pull our personas out of thin air, and he’s right that many of us wring our hands over how we aren’t doing enough research to back up our work. Our faithfulness to understanding real user needs is the backbone of the information architect’s identity.

My contention, though, is that the vast majority of us really don’t need to be quite as scientific as Steve recommends.

Persona Creep

Don Norman often uses the term “creeping featuritis” to describe what happens when we add features to a product without basing those features on what people actually want and need. This would seem to be a convincing rationale for creating deep, complex user personas, right?

Maybe not. If you view the user personas themselves as a product, and the product design team as users of that product, you wouldn’t necessarily reach the same conclusion. The level of complexity, detail, and scientific “truthfulness” of a user persona is a factor of context: Who is ultimately using the personas and how, and what the schedule and budget are.

If personas are going to be used to help a thirty-person team build a multi-million dollar web site, spending a month or more doing the research to build scientific personas makes a lot of sense. But for a five-figure web site, a development team may only be able to budget a few days for persona creation. For smaller projects, maybe even less than a day.

These are sample Cooper personas from 1998. They’re lean and mean. What happened to these?

In fact, when Cooper introduced the persona concept, personas were breif to-the-point sketches. Those are what we fell in love with back in 1998. But look at what’s happened since then: User personas have bloated out of control! What started out as simply a name, a photograph, and two or three short paragraphs of text have turned into virtual FBI dossiers and employee personnel files, replete with citations, numbers, charts and graphs, and reams of text.

For big projects, complex personas might be perfectly appropriate. But all too often smaller, low budget projects end up making a tough choice: Clients and teams doubt the value in building and using personas that lack a strong research foundation, so they simply skip them entirely.

Getting Real with Rapid Persona Modeling

To latch onto the buzzword du jour, I think it’s high time a lot of us “got real” about personas, and attack them with a little more flexiblity. While the 37 signals crew would probably skip personas entirely, I think personas incredibly useful even for small teams and small- to medium-sized projects, even if they’re not firmly based in research, even if they’re largely “made up”. If produced by team members with even a little bit of insight into the product’s users, they’ll still help a team’s understanding of what’s right and wrong for the product, and are certainly better than just not doing personas at all.

What we need is a professional toolkit and a respectable discourse to support a rapid- or guerilla-based persona modeling approach. I fear there’s a lot of resistance in the IA community to this, however, but I hope I’m wrong. Steve Mulder’s approach is great, but it’s not for everyone or every project and by no means should our admiration for his tools mean that alternative, possibly less scientific, approaches aren’t incredibly useful, too.

Don Norman, by the way, agrees with me. He calls this approach “Ad-Hoc Personas” (ironically, this is a sidebar in a book dedicated to the idea that personas must be grounded in user research):

Do Personas have to be accurate? Do they require a large body of research? Not always, I conclude. The Personas must indeed reflect the target group for the design team, but for some purposes, that is sufficient. A Persona allows designers to bring their own life-long experience to bear on the problem, and because each Persona is a realistic individual person, the designers can focus upon features, behaviors, and expectations appropriate for this individual, allowing the designer to screen off from consideration all those other wonderful ideas they may have. If the other ideas are as useful and valuable as they might seem, the designer’s challenge is to either create a scenario for the existing Persona where they makes sense, or to invent a new Persona where it is appropriate and then to justify inclusion of this new Persona by making the business case argument that the new Persona does indeed represent an important target population for the product.

I’ll be writing more about this in the future, but I’d love to hear what you think about these ideas: Do you use personas at all, or do you skip them because they’re too much work, or because you think they’re just too phony? If you use them, do you do a heap of research, do you make em up out of thin air, or somewhere inbetween? Leave a comment, or reply to me offline, if you prefer (askrom [at] graphpaper dot com). Thanks!

UPDATE: Closed comments. This post is somehow a spam-magnet. Weird.

Comments

12 responses to “IA Summit 2006: The Science (and Pseudo-Science) of Personas”

Hey there,

Nice thoughts. I’m wondering if you took a look at that Norman article on “Activity-Centered Design” and if you think it offers anything useful for persona design.

I think activity-centered design sounds great, although I’ll admit I don’t fully understand it, and that it’s still an idea in its wobbly infancy. It sounds a lot like giving a name to what I would call “design inspiration”, the part of the design process where the designer invents the basic way the interface is used, the “feel” part of “look and feel”.

An important point to me is that it does not need to be mutually-exclusive from traditional persona work. We should incorporate ACD into personas somehow (going beyond traditional tasks and goals). Perhaps it’s an opportunity to describe activities within the context of a persona, but not as subsections of the personas: perhaps rather as separate, experimental, more innovation-focused documents.

Does this mean we can design with multiple centers? I guess so. Like an ellipse.

By the way, I’ve learned over the past week that Don Norman is the man. We’re on the same wavelength a lot lately it’s creepy. Thanks for reminding me of the ACD approach — it’s totally relevant to the idea of guerilla personas.

Now you’re just showing off. Great read, Chris.

great post. I’ve been talking a bit with a few people lately about personas and their value to the process.

I also see problems with personas, including the ‘no good without extensive research’ attitude, but one that I find even more dangerous which is ‘making personas a little bit too late in the game so that you’re actually matching them to a solution you already have in mind’.

I think that sometimes, personas can be done as an afterthought to ‘fill in’ process and ‘prove’ an approach… this makes personas pretty useless.

Having said all that – I’m a big fan of the ‘ad hoc’ persona approach. My experience with overly researched personas is that they don’t really add much value to the process and often result designers/clients getting all caught up in tiny details that actually don’t really matter!

At the end of the day, it’s all about keeping the design approach centred on the user and their aspirations… so any tool that can help maintain that focus is a good tool.

p.s. is it just me, or does anyone else think that it should be personae and not personas?

my book is now so much more worldly than me. 😉

you know, chris, when khoi and i redesigned mediamatters, i emloyed a guerilla style of persona/scenario development (completey against the teaching of david fore at cooper, might i add).

because we didn’t have access to either quantitative, market research (stereotypical profiles with stereotypical needs) nor a budget/timeline for running qualitative interviews (to turn the stereotypes into archetypical design personas, based on synthesized behavioral patterns and iterative modeling) we decided to based our design persona development on the perspective of a cross-section of media matters staff.

the result of that first exercise was a very detailed segmentation document, with motivation and context covered to a certain degree of specificity. from that exercise, i was then able to merge these better-than-stereotypical-segments down into a smaller set of design personas… and then down into context (which i somewhat equate with ACD) and key scenarios.

it would’ve been great to have 15 – 20 people — journalists, bloggers, activists, hill staff, etc. — at our disposal to interview, but our mock persona / scenario process established a pretty strong stake in the ground for MM’s initial redesign and for building upon moving forward.

takeaway: if you’re not designing a healthcare or security application (i.e. life and death dependencies), you can fudge the method and get really, solid results with a little investment of time. it’s like getting real without completely guessing.

Sean: Heh, hope you don’t mind my image appropriation!

And yes, the law of diminishing returns is powerfully apt here: You can spend 3 days making ad-hoc personas to get them to 75% accuracy, or spend two months to get them to 90%. If you’ve got the budget and the time, and the project is critical enough, the two months might be worth it. If not, go for the 3-day model and feel glad that you didn’t skip personas entirely, because they really do help.

nah, dude, it’s hilarious that you picked it up. john has me rolling with his shots…

I agree that for many organizations, guerilla personas are the way to go. My intent in the presentation was to outline the “Lexus” of persona creation methodologies. Not everyone needs or should own a Lexus, of course. But if you have stakeholders who demand “proof” before they buy into your personas, the quantitative approach can be amazingly valuable.

On the other hand, I also believe that even guerilla personas could benefit from a wee bit more contact with real users. Interviewing ten users takes almost no time, and grounds the team in the needs of real people. If I can help it, I’ll never go back to creating personas without doing at least a little qualitative research.

Steve: Thanks for visiting!! I think you presented a broad range of powerful research (and creative) tools and techniques which, when added up, make a Lexus. One can clearly use a few, a lot, or all of your suggested methods to help make personas better.

Your comment “if you have stakeholders who demand “proof†before they buy into your personas” suggests that, to varying degrees, part of the motivation for us to build “scientific” personas is to please stakeholders who may not trust the value of the exercise without seeing that kind of statistical basis. I’m not saying this is the only reason, but I suspect that in many cases it’s a big factor in the decision to go increasingly scientific with personas.

(This goes all the way back to the sales cycle, where we think we can’t “sell” the personas exercise to a client unless we convince them they’re scientifically sound, sometimes forcing consultants to plan for more robust, costly, and time-consuming persona work than may be actually necessary for the project. I’ve had clients (smart clients, people familiar with the value of personas) who chose to drop personas from the project entirely because they saw it as a binary decision: expensive research-based personas, or none at all.)

Your point about at least conducting some sort of interviews, however, is absolutely correct. I’d say that for making useful personas, user interviews are more powerful than all other types of quantitative research combined.

But there’s a fuzzy area around “user interviews”: On some projects, I’ve interviewed a dozen client salespeople and/or customer service reps instead of talking directly to customers, resulting at least in a far better view into the user base than what we could have made from thin air or by simply talking to one client stakeholder. It would have been better to talk to real customers/users, of course, but finding a dozen representative users, with the correct balance of demographic and/or functional diversity, would have been far, far more costly (recruiting, screening, scheduling, validating, etc.) and I question whether or not it would have added a whole lot of accurate insight anyway.

This overview, while excellent, continues a fantasy that is not productive for real people trying to put real personas in place.

I acknowledge the value of personas, if only to make it possible to have a way to empathize with the potential goal and behavior of a given type of user when looking critically about interaction design.

However, there are two major issues that have to be tackled:

1. The idea of doing an exercise in a room with some interviews to discover persona’s is a friendly process, but should not be allowed to take much time, as it does not benefit from rigor. In the end, persona’s must be found, not “designed”, and they can only be found through iteration of concept (from the room) and execution (with real customers interacting in the real world, not the lab).

2. The major, major, major flaw of personas is that it is exceptionally difficult to identify whether a given visitor or user fits into one of the personas during the actual use of the site or service. You can create beautiful charts and pictures and go to endless listening labs, but it won’t tell you how to recognize the person by their actions.

What is the net of all of this? Don’t think of Personas as another “up-front” process for “understanding” customers, like focus groups. Don’t use them to “design” the experience.

Think of Persona’s as folders into which you can put ideas to try, insights you gather, and results of tests on real visitors. Work on how you are going to identify different types of users/customers in real time, how you are going to test ideas, and how you are going to think up new ones.

Matthew:

In the end, persona’s must be found, not “designedâ€, and they can only be found through iteration of concept (from the room) and execution (with real customers interacting in the real world, not the lab).

You’re writing as if the point of personas is to “find” who your users are, uncovering an existing reality like “finding” a new planet. What you’re talking about is a useful thing, but it’s not personas. The purpose of personas is, as you say, “to make it possible to have a way to empathize with the potential goal and behavior of a given type of user”. To claim or to hope that personas do much more than that is pretty ambitious, if not downright folly. I think any tool that gives the design team empathy for the user is a major, major step forward for almost any project, and I don’t quite get why everyone seems to think that that’s not enough.

it is exceptionally difficult to identify whether a given visitor or user fits into one of the personas during the actual use of the site or service

Again, I don’t understand what you mean. I’ve never heard of anyone trying to figure out which post-launch users “fit into” which pre-design personas. That’s like trying to identify which dressmaker’s dummy corresponds to each customer who walks into a clothing store. Personas aren’t really intended to be used for evaluating or tracking real users. They’re used for evaluating ideas before you show them to users. They’re design tools.

on your blog you write:

I am very pro-analytics, but the fact is we stink at predicting the future even with vast information from the past. Whether you are talking about new products, email copy, ads, or landing page optimization, the only way to truly know what the customer will do is to put it out there and watch what the customer does.

You were writing about marketing ideas, but the same could be said for personas: Personas are useful for helping generate and/or validate design ideas before you build something. Then you can build your ideas and try them with real users (in the lab or in real life) and see how it worked and learn how you can revise and improve the ideas. The prototype–> test–> iterate cycle is still valid and powerful, and the use of personas, no matter how ad-hoc, in the early stages of the design process shouldn’t change the value of that cycle.

Anyway, I don’t understand how you can say “Think of Persona’s as folders into which you can put ideas to try” and “Don’t use [personas] to “design” the experience.” Doesn’t the first sentence describe “design”? It sounds like you’re skeptical of personas because you think of them as being used for something far different, or far more, than what I think most people think they are useful for.

Chris,

Thanks for the nice summary of personas, and thanks to the folks posting comments for a great discussion. Just a couple of comments:

“Ad hoc” personas are not a new discovery. We used them at Cooper used from about 1997, referring to them as “provisional personas”. While it was never the preferred method, sometimes they were simply a necessity borne of circumstance: there was simply not enough time or resources to perform the necessary field work.

There are however caveats: while provisional personas may help focus your design and product team, if you do not have any data to back up your assumptions you may:

* focus on the wrong design target

* focus on the right target, but miss key behaviors that could differentiate your product

* have a difficult time getting alignment from individuals and groups who did not participate in their creation

* cause your organization to reject personas (or full personas) in the long term

If you are using provisional personas, it’s important to:

* clearly label and explain them as such

* represent them visually with sketches, not photos, to reinforce the above

* try to make use of as much existing data as possible (market surveys, domain research, subject matter experts, field studies or personas for related products)

* document what data was used, and what assumptions were made

* steer clear of stereotypes (harder to do without field data)

* focus on behaviors and motivations, not demographics/technographics (again, harder without the data)

“Activity-centered design” is also not particularly new. Cooper has been calling it “Goal-Directed design” since 1995. The primary difference is that GDD takes a further step back from both tasks *and* activities to focus on user goals and motivations first, and from this define the ideal high level interaction (activity) for accomplishing the goal(s).