I am a 37-year-old user experience designer, and I don’t have a driver’s license. I don’t even know how to drive a car. I moved to New York City when I was 18 and I just never really needed to learn.

Moreover, I don’t even find automobiles all that interesting or seductive, at least not the ones I see on the streets today. They’re certainly not, as they were a half-century ago, a glimpse into some hopeful and mind-boggling future. Rather, to me, the automobile is a symbol of a bygone era of American industry, culture, and lifestyle.

Because of my obvious dispassion for car culture, I think I can offer an unconventional and hopefully useful perspective on the struggling American auto industry.

I mean, everybody else seems to have a theory about how to save Detroit. And I’ll admit that I find myself reluctantly sympathetic with those who are calling for a radical, technology- based transformation of the business. Whether admonishing the industry to “Stop Building Cars“, encouraging a conversion to a design-based auto industry (some flat out asking “What if Steve Jobs ran GM?“), scolding the automakers while debating bailing them out (it’s amusing to hear Senator Richard Shelby chiding the automakers for their lack of “inn-o-vation” in his Alabama drawl), or Andy Grove pushing Intel to invest in critical battery research for electric cars, it’s clear that many people think the American auto industry’s ultimate salvation will be in cutting-edge technology and design.

I find myself frequently nodding my head at these suggestions. The tech geek in me agrees that there is something the tech business is doing right that the auto business is doing wrong.

What is it? Well, it’s two things.

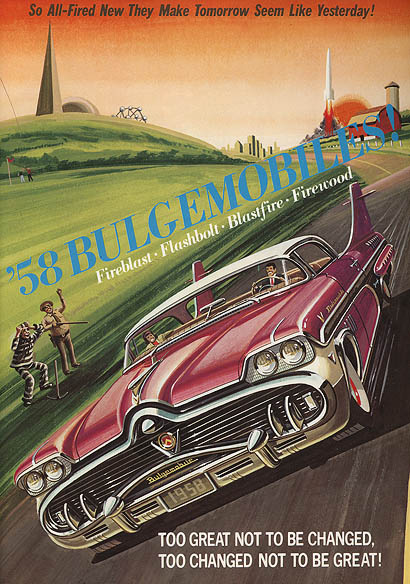

The ’58 Bulgemobile Catalog, from Bruce McCall’s Zany Afternoons.

Design

The first problem, what everyone focuses on, is the product itself. The design. The whole “car experience”, which really hasn’t changed much in decades. AFAIK, the only truly important developments in the last 25 years have been hybrids and GPS.

And from the industry’s perspective the most significant and successful design innovation has, ironically, also been the instrument of its recent decline: the outrageous and gluttonous giganticness of SUVs (which really isn’t all that innovative when you consider the gigantism rampant in automotive design of the 1950s).

It all seems so dead to me. My desire to learn to drive — to the extent that it exists at all — feels on an emotional level similar to my desire to smoke a cigarette, own a beeper, rent a videotape at Blockbuster, or sign up for 600 free minutes of AOL. Which is to say that the whole idea (of driving!) seems silly and old fashioned and lame.

It’s easy for me to imagine a hundred ways that cars could be better — from energy efficiency to user experience to aesthetics, or even fundamentally rethinking the infrastructure of highways and roads and parking. Plenty of other people are also describing Detroit’s many design and technology shortcomings elsewhere. If it were not for the fact that the auto industry is still an integral part of my country’s economy and the livelihood of millions of Americans, and if the auto business hadn’t in previous generations worked at technology’s bleeding edge, I’d be completely apathetic about the whole question of automotive user experience design.

Unlike many of my peers (most of whom drive, of course), I can barely muster up enough interest in the fate of the auto industry to bother to speculate about the details of how cars might be improved from a design perspective. It’s like trying to get excited about designing a new kind of whaling harpoon or devising a new kind of portable CD player. I mean, who cares? What good will it do?

But that is precisely the problem: How can we expect innovation from Detroit when creative and technology workers like myself have no desire to lift a finger to help the automotive business? And forget about me, middle-aged and settled in my web career: Why should a 22-year-old technology or design whiz kid want to build cars when they could be working with far cooler, more exciting, and less environmentally-damaging technologies?

Designers

Don’t get me wrong: Plenty of extraordinarily talented and inventive people work in the auto industry. But it’s just not at the same level as the excitement and innovation we see in design on the web, on our mobile phones, and on our desktops. It doesn’t resonate with the public imagination.

I ask myself this question: “Would I want to work there?” Or one of my friends and colleagues? A talented young software engineer? A recent design-school graduate? As a future-thinking knowledge worker, someone like me should be strongly tempted to work for an auto company.

The biggest problem is not that the auto companies are making products consumers don’t want — people will continue to buy cars and muddle through the lackluster design and user experiences, the outrageous fuel costs, the physical danger, and the unconscionable pollution. No, the real, long-term problem with Detroit is that the automakers are just not the kind of companies the next generation of innovators will want to work for.

I don’t know the answer to this, particularly from a public policy perspective, but it’s important that we all frame the real question correctly. It’s not about the design, it’s about the designers. It’s about the workers.

(NOTE: I hate to seem sympathetic with the techno-futurist camp. There’s something terribly elitist about scolding Detroit for not being like Silicon Valley. It’s unforgivably crass to suggest that we just let the automakers precipitously fail and let their workers drift into unemployment and poverty. There is knowledge and talent in the industry today, know-how that needs to be used to make the new auto industry even better. A sudden lurch into industrial calamity, with an eventual triumphant rebirth in California garages, sounds like an idealistic and romantic story. But it’s not so romantic to the hundreds of thousands of people without a paycheck. The solution needs to be driven by practical needs, not dramatic storylines.)

Comments

9 responses to “Designed in Detroit by General Motors”

You’ve provided an interesting angle on the whole debacle with Detroit. I do agree that technology and innovation will definitely play a role in the redemption of the Big 3.

By talking about the new employees perspective, you’ve approached from an entirely new angle what I feel is the core problem– there is no one else to blame for the Big 3’s current malaise except their own short-sighted management. Not since Britain’s economic dependence on slavery in the 1800’s has big business gone so far in betting on the wrong horse (specifically, counting on the fact that oil would stay cheap).

What makes it worse is how not just one major American corporation, but 3 major corporations, have diversified so little over 10 years from their core focus on gas guzzling, expensively made, inadequately QC’ed, disposably designed, carbon inefficient light trucks.

It’s representative of their philosophy to point out that the same year that GM bought the rights to build Hummers, they recalled and destroyed all EV1’s (the first practical American electric car.)

To bring this back to your thesis, even the teams who design concept cars for GM and the rest of the Big 3 have been focused on the same old vehicular models with only superficial deviations. Few adventurous industrial designers would seriously think they’d find the freedom to innovate in an environment like that.

Originating in the Cleveland area I know first-hand the economic catastrophe that would ensue if the big 3 went under. I have many friends and family that work at, have worked at or are retired from Ford Motor Co. (More than I can count on two hands.)

I’m pro-bailout for auto. The main reason being that I’m afraid of what further degradation the so-called rust belt will experience if the auto industry goes under. Plus, it’s just fucked that we can toss 700 billions at the finance industry without blinking an eye, but when it comes to a blue collar industry — asking for much less $$ — suddenly we need to have them go it on their own. A bit of a double standard there… bail out the bankers, let the blue collar workers fail.

Interestingly, my mother (still residing in the Cleveland area) is all for them going it on their own (that was very surprising to me). Perhaps she’s just naive about the devastating impact a failure of these companies would have? Perhaps she has better knowledge? I don’t know…

Chris,

It’s interesting to hear your perspective on cars — very rare to hear the voice of an outsider to something as shared as the culture driving in the states. Still, it’s frustrating to hear your contempt for the auto industry, given that you don’t have any need for a car at all.

The tone of your article assumes that you represent a unique, interesting consumer who the automakers should want to target. But isn’t this just a bit unrealistic? You state in your article that you have no need whatsoever, for a car. But the vast majority of Americans need cars for transportation. In cities, suburbs, rural areas without viable mass transit, a car isn’t a choice, but a necessity. Even the worst cars serve this function well (they get you from point A – B).

Would you ever advise a client that you should be designing a website or interface to consider the whims of someone who doesn’t ever use a computer, or have a need to? Of course not — you design your work to meet the needs of those who use it. I doubt the problem of “getting more people to drive” is really a problem that needs to be solved (if anything we should be trying to get less people to drive, right?).

The other point you seem to be making is that cars aren’t cool enough for people to be drawn to designing them as careers. While I can see your reasoning, isn’t it hard to be blinded by the fact we’re lucky enough to work in a new, still incredibly young and exciting industry? For those who aren’t drawn to the web (maybe they hate being in front of computers all day — I do), but are instead drawn to solving complex, physical engineering problems, working for an auto company represents a huge opportunity to affect change and to put your work into hands of so many. Don’t you think the team that designed the Prius feels excited to have jump-started a green movement and created one of the fastest selling eco-friendly cars in history? Perhaps that team has done as much to curb pollution as thousands of Sierra club canvassers.

Really, my annoyance with the line of reasoning that the auto companies are failing “because they don’t make cars people want to buy” is simply not true. Just five years ago, all big three auto companies were making historic profits, selling at cars at near full production capacity. They were most assuredly satisfying demand. Did the demand change? Yes. Did gas prices nearly double in a historically short term span? Yes. Did the public awareness of global warming finally take hold? Yes. Did we have the single largest financial failure in decades at a time when auto demand, across the board was fading? Frighteningly, yes.

In the end, absolutely nothing about the current state of the US auto industry is simple — there are no easy answers to what caused things to be how they are now, or how to fix them. It’s a wildly complex set of issues that caused by a combination of distortive government policy, non-optimal labor negotiations, poor managerial leadership, combative parts-supplier relationships, regional politics, legacy manufacturing processes, changing demand in a horribly unfavorable economy — all in an industry that has incredibly low-capital mobility, making change difficult and costly.

Detroit didn’t fail just because of a lack of heart, fresh thinking, and depleted “innovation mojo.” They failed because our needs are changing as a country, the industry is costly and difficult to change, and because our government, CEO leadership, and the Unions failed to resolve the lingering issues decades ago.

@Matt Brown: I hope I didn’t convey any “contempt” for the auto industry. I’m simply not impressed with them, and I think the industry is something that should impress me.

Also, I wasn’t arguing that the industry wasn’t making what people wanted. Plenty of other people have done that, and I reference them, but I’m not on board with that idea. They made SUVs because people wanted SUVs, and they made buttloads of money. Obviously I think SUVs are hideously irresponsible and unsustainable, both from a business and an environmental perspective, but I would hardly argue they weren’t what people wanted.

The problem is that the industry should be making what people never knew they wanted. They should be ahead of the curve. The only reason we have hybrid cars at all is because governments mandated them — against the industry’s will. It’s probably important to note that the Prius was a surprise hit. They really didn’t believe people wanted it. There is clearly a major disconnect between the marketers, the designers, the regulators, and the consumer.

Finally, I am not blaming “the industry” for this. Nor the unions. The auto industry, if we want to have one at all (and I definitely think we should!), is everyone’s responsibility. The auto industry would never have bet the farm on SUVs (even if everyone wanted them), and they might be ready to roll with better hybrids and electrics and gas-efficient vehicles, if they were in sync with smart government policies and the long term public zeitgest. But NONE of this would be possible without everyone agreeing on the mission — everyone, including those who make the public policy that helps shape the direction the industry moves so that they aren’t simply responding to short-sighted consumer demand.

I don’t buy the victim of the financial crisis argument, either. Yes the crisis precipitated today’s Big3 crisis, but I’m talking about the longer term. I’d make this argument even if there was no crisis: It’s hard to imagine that the auto industry, anywhere in the world, is anywhere near prepared for the day when oil reaches $150 or $200/barrel permanently, which at this rate will happen before we are ready for it. In my view oil is priced artificially low, and was still artificially low even this spring when it spiked to record highs.

The solution for the auto business will, fundamentally, entail a transformation of our society at almost every level. My point was simply to focus on the recruitment and cultural appeal of the auto industry for young entrepreneurs and innovators, people who see the world’s oil running out, the roads falling apart and wonder if fresh ideas would really be welcome in the auto business.

As a follow up, I do really like your point that it is about creating a demand for the designers and workers — if this industry is seen as a doomed, dead-end career, we’ll never find good solutions to the problems we face.

Still, I’m not sure that there is a lack of supply at these companies for talented automotive designers. I’ve never read anything about companies not being able to source good talent. Really, it’s more a function of it being very risky to release bold designs as production cars — new designs are *incredibly* expensive to produce, so no one wants to risk a flop. That’s why all cars look so damned bland and similar.

Anyway, I’m definitely in agreement that there needs to be a desire to fix these problems and, if we’re going to have a functioning, vibrant auto industry, we need good minds and a passion to solve these tough problems.

@Matt Brown: It could just be that I live in a web-design post-industrial non-car-lovin’ bubble. That’s quite likely. I suppose that’s why I got that out of the way in the first sentence! 🙂

Point taken, too, that there may already be thousands of exactly the kind of innovative thinkers in (and trying to get into) the auto business. People who love cars and want to change the whole automobile world and point them in the right direction, but who lack all the support structures — in business, government, and culture — to let them thrive. I’ll buy that argument, too.

chris, these are the bomb:

http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2008/12/how-to-save-detroit/

Chris –

I agree with the sentiments expressed here, and I think I’ve wondered how things got to be this way. I don’t think it has much to do with “Detroit”, but more to do with the nature of very large, heavily regulated companies that make very expensive, highly visible products. This is a mature industry in many ways, with deeply entrenched systems and cultures.

I often wonder how Hollywood can produce such horrible products, but then look at the credits – look how many people it takes to make a movie (it really doesn’t take that many, as YouTube hints at). Consider how many more people were involved that don’t show up there – investors, marketers, etc. who influenced the success of the film.

Having worked at a big technology company, I’ve seen many of the same things happen. Typically, though, the stakes are far lower online than in the physical world. I actually consulted for Ford at one point, and saw enthusiasm and dedication, but also the mind-numbing culture of a mature large company.

Its a separate discussion, but American car companies aren’t the only ones facing this crisis, and unfortunately, we’ll probably see more industries in the same boat in the next year.

Neil

@Gong: Two pages before the Bulgemobile image above, Bruce McCall painted an old K-car treated just like the cars in the article you link. I’ll try to get a scan of it.