In a previous post, I mentioned the “Technologies of Writing” show I saw during SXSW at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center. Since then, I’ve had several occasions to think about the exhibit again. So I thought I’d go a little more into some of the highlights from the show and share some of the related thoughts that have come up since then.

Before Writing

The first thing I learned when I entered the exhibition was this: Before there was any form of language-based writing at all, some early Mesopotamians used clay objects of different shapes to represent recorded word-based information. One would collect a small bundle of these objects and somehow, taken together, the group of objects would form a message.

Presumably the messages contained in these clay trinkets were somewhat prone to inaccuracy. For example, if you switch the order in which you read them, a message such as “Marduk owes Ishtar thirty shekels” could easily become “Ishtar owes Marduk thirty shekels.”

To correct for this, they started making little incisions in the clay. Soon (and by ‘soon’ we’re talking many hundreds of years) these incisions evolved into a whole new writing system. The world’s first writing system, in fact: cuneiform.

Meanwhile, in Europe

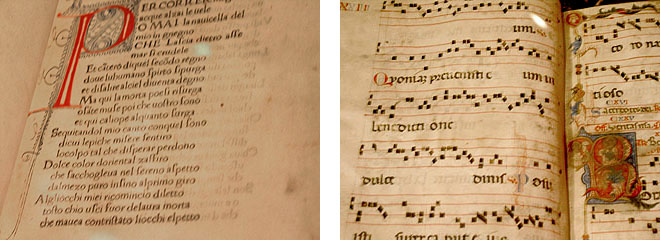

There were also some great examples of early European manuscripts, in which you can see some of the origins of modern typography emerging from the hand-written tradition, as well as clearly originating from annotated imagery (that is, incuding text with images, such as in the Bayeux Tapestry).

I especially loved the early musical scores: Part of the history of writing and language is our history of encoding music. It’s hard to separate the two, in fact, when you consider the importance of the oral tradition, which usually involved some degree of rhyme and melody, before there was the written word. Much early literature is in fact written in rhyming verse, as seen on the right (I love the reverse indentation of the first lines). Many of the earliest Bibles include little typographic indicators and clues for how to sing each passage.

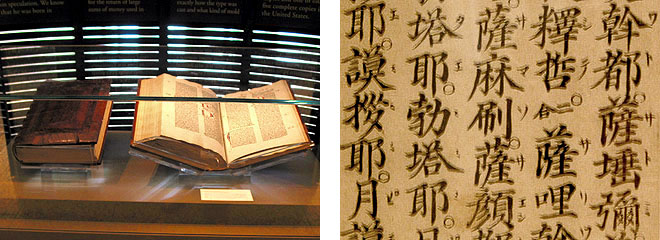

Movable Type

The Ransom center has a Gutenberg Bible in their permanent collection. Gutenberg is well-known to have been influenced by movable block type from China, but he clearly took it to a whole new level. After viewing dozens of hand-written mideival manuscripts, the Gutenberg Bible almost seemed to me like yet another work of a careful monk’s patient quill. Much of the book is, of course, illustrated and decorated by hand. But the printing itself is so careful and so beautiful that it’s hard to think of it as machine-made. In fact, printing a Gutenberg Bible was an incredibly time-consuming process, taking many months to complete. Not as bad as copying by hand, but not a whole lot better, either.

I once read that the earliest transatlantic cable transmissions were so faint and hard to detect that it took many hours just to successfully communicate a single short sentence. Much like the early days of home computers, where a few dozen kilobytes of code could take minutes to save to cassette tape, it seems like many new technologies are at first barely an improvement over their predecessors, especially when compared to where they eventually end up.

Modern Manuscripts

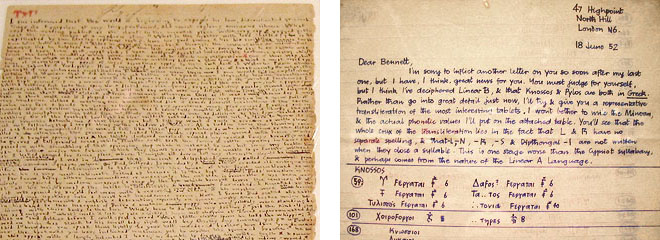

Some of the most interesting materials in the show were the more contemporary original manuscripts from 19th and 20th century scientists and literary figures. On the left is an example of Charlotte Bronte’s handwriting for her novel The Green Dwarf. The page you see is about three inches across, probably about the same size as what you’re seeing on your screen. Yes, she wrote entire novels in 2-point script.

On the right is a letter reading, in part “I think I’ve decyphered Linear B”. How cool is that? — being able to just casually write a note to a colleague saying that you’ve decoded the world’s most baffling ancient language.

Eat Your Heart Out, Edward Tufte

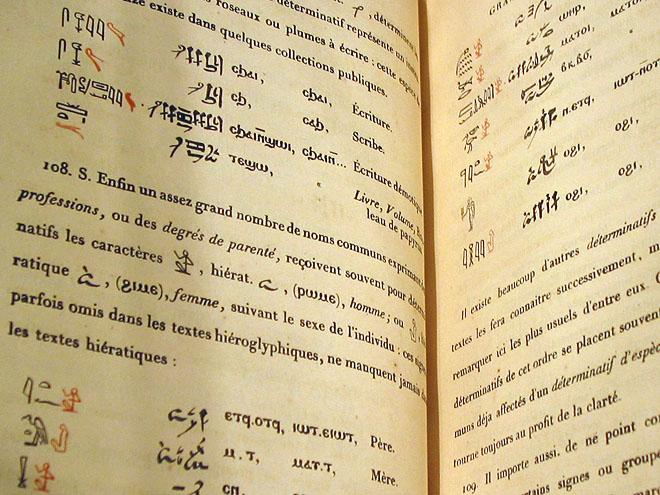

This French book of hieroglyphic interpretation (below) is a stunning, simple, and elegant blend of typography and illustration. That is, if you can call hieroglyphics illustrations — are they not also typography?

My favorite peice in the show, however, was probably the sample of Gertrude Stein’s personal stationary, which had this wonderful little embossed rose in the corner (about a centimeter in diameter), and a tiny little inscription with her famous address, “27 Rue de Fleurus”.

[For more photos of the artifacts in this show, check out Liz Danzico’s Flickr gallery. She had a better camera than I did, I think, and was far brasher about violating the Ransom Center’s “no photography” rule.]

Coincidences and Connections

As fate would have it, Don Norman has just written a short but interesting article in Forbes touching on the very subject of writing technologies:

The power of the unaided mind is greatly exaggerated. It is “things” that make us smart, the cognitive artifacts that allow human beings to overcome the limitations of human memory and conscious reasoning.

And of all the artifacts that have aided cognition, the most important is the development of writing, or more properly, of notational systems: number systems, writing, calendars, notational systems for mathematics, engineering, music and dance.

This concept made me think of a great old article by Andy Clark which posits, among many other things, that humans are essentially cyborgs already. Not just because we use tools, but because (as Norman says above) we specifically use tools and technologies to help us store knowledge and share it among ourselves. A human augmented with language and writing is fundamentally different than one without those augmentations. Such a human is a kind of cyborg, says Clark. He continues this in his book Natural Born Cyborgs, which I intend to read someday.

Not surprisingly, when I Googled Norman’s and Clark’s books together, I found them to be on a lot of shared reading lists. It’s great to make connections like this — from SXSW to the origins of writing to Don Norman to cyborgs… full circle!

Comments

2 responses to “Writing Technologies: From Cuneiform to Cyborg”

Damn, if I had known about this show while I was in Austin, I would have been there in a heartbeat. Your writeup summarizes a lot of great info really well, though, so at least I can live vicariously.

Hey Rob, I think you would really have enjoyed it. I wish that it would travel around, it would make a great touring show.

The Morgan Library is about to re-open in New York at the end of the month, with huge amounts of new space and new exhibitions, and some truly stunning new architecture. I supect that the Morgan Library’s opening exhibits would be pretty amazing. Come up to NYC for a field trip visit!